Former MNA Serge Ménard recalled Laval’s rural past on its 40th birthday

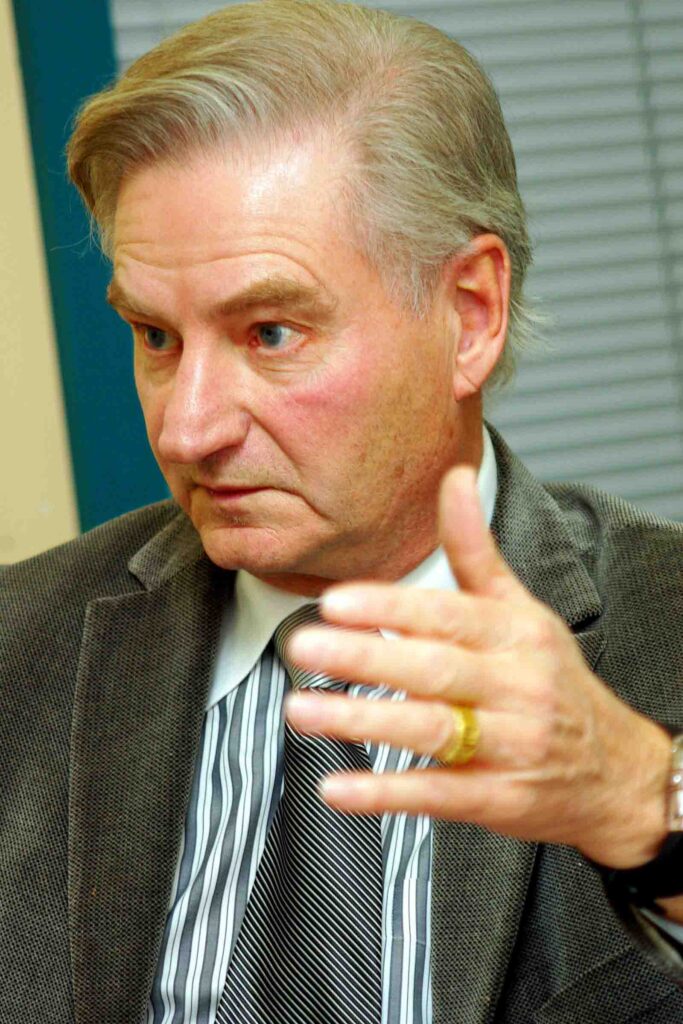

As many as 32 individual municipalities once dotted the countryside of Laval in the decades preceding the formation of the island-wide city in 1965, says former Marc-Aurèle-Fortin MP Serge Ménard. Ménard, who spent his boyhood summers bicycling and swimming at his family’s country home on the Rivière-des-Milles-Îles, recounted some of his memories in view of the City of Laval’s 40th anniversary. The Laval News here republishes an interview conducted with Serge Ménard in 2005.

Serge Ménard has vivid memories of Laval before it was a bustling suburb – a golden age when it was still largely a rural retreat for Montrealers getting away from the oppressive city heat in the summertime.

“I can remember when I was a small boy, Laval was essentially cottages and farms,” the Bloc Québécois MP for Laval’s Marc-Aurèle-Fortin riding recalled recently for The Chomedey News on the occasion of the City of Laval’s 40th anniversary.

“There was a great deal of agricultural activity and a lot of fields,” he said. “Today it still has that agricultural quality. Notably, we are one of the best known flower gardens – not only in Quebec – but in the northeastern region of North America.”

Around 1955, when Ménard was a high-school student in Quebec’s ‘cours classique’ educational system, his father decided to build a summer house in Laval for his family, who were living in Montreal’s Plateau-Mont-Royal district at the time.

“I was 15 when father built a summer house on the Rivière-des-Mille-Îles. It was right next to Jacques Cartier Beach, which was right next to Laval’s (public) beach. It’s still inhabited – 1 Val des Bois.

“That’s the house father had built,” said Ménard. “It was a summer cottage which was subsequently redesigned to be a year-around residence. In fact, the people who bought it and live there now live in it all year long, as do most people in that area.”

Ménard, who has never resided in Laval except during the summers of his youth, has represented constituents here since 1993, when he was first elected to the Quebec National Assembly for the Parti Québécois. Although he’s never been a full-time resident, he said his memories of the island during the summer have remained strong.

“I knew Laval during the summer, and I knew it from the vantage point of a bicycle – because, when eventually my father allowed me to get away from the house on two wheels, that was freedom,” he said, laughing. “I must have gone to every corner of Laval.”

Ménard recounted how, when he was a bit older, he worked two summers at the Hôpital du Sacré Coeur just across Rivière des Prairies from Laval in Montreal. He would travel daily from the country home to the hospital on his bike.

“I would do that by bike morning and evening,” he said. “From One Val des Bois, it would take about three-quarters of an hour. We also had a row boat and there was swimming, too. We went swimming and fishing. We were right next to a beach so we would see people who came to swim.”

But if Ménard has mostly happy memories of those bygone days, he also has at least one unpleasant one.

“Because we were beside a beach and saw people regularly who came to swim, among the most traumatic things a boy that age could ever see, I can tell you, was when the priest would arrive to tell children or a wife that their father had probably drowned,” he said.

According to Ménard, there were a lot of drownings off the beaches of Laval in those days.

“I remember there were some every weekend. It was because people weren’t taking precautions. Our parents used to tell us in those days, ‘You see what happens to people who don’t wait three hours after eating before they go swimming.’ They always used to tell us you had to wait three hours.”

Besides his personal recollections, Ménard vividly remembers the political turmoil that surrounded Laval’s beginnings as a city in 1965.

“I can’t help but remember the controversy over the creation of Laval – about the same as the one that surrounded the recent municipal mergers,” he said, referring to the City of Montreal’s controversial amalgamation process recently.

However, he added, once Laval’s amalgamation had been completed, it soon became a “collective success,” with important sectors such as the pharmaceutical industry playing a dominant role.

“It has become a place to live where people have all the advantages of a large metropolitan region, but also the outdoors and lots of room for children to play; a very comfortable and safe place to live.”

In hindsight, Ménard believes that the merger of the 16 small municipalities that were on Laval Island in the early 1960s, into one large city in 1965, succeeded mainly because of the determination of the provincial government, not only to carry it out, but to make sure it would hold long after it was done.

“(The merger of) Laval was done very quickly,” he said. “It was done at the end of (a National Assembly) session. There was a commission of inquiry – the Sylvestre Commission. I remember even at that time, Mayor Jean-Noël Lavoie had already brought about the merger of three towns to create Chomedey.

At one time, according to Ménard, there were as many as 32 independent municipalities on the island.

“But you have to understand that this was relative to the fact it was in an era when villages surrounded a local church. It was a time before the advent of the automobile, or just at its beginning, when that mode of transportation was available only to the wealthy. The main economic activity was farming. For that matter, Laval still has some of the best land of its kind for agriculture.”

Looking towards the future, Ménard sees Laval remaining one of the driving forces in the economic development of the Montreal metropolitan region – somewhat like the relationship the U.S. city of Boston has with its surrounding suburbs.

“And with the arrival of the Metro, that will probably also encourage development, too,” he added. “I think the Metro is going to influence the development of a downtown core in Laval.”

At the same time, he said caution would be necessary to prevent indiscriminate development from allowing uncontrolled high-rise construction. “I hope we will always be able to have urban development plans that have humane height restrictions – a little like what they have in Washington, D.C,” said Ménard.